By Gussie Fauntleroy

Burt Wadman was a very inquisitive 5-year-old when a friend who lived next door in rural Long Island, New York, decided he wanted a small playhouse. The boy’s older brother agreed to build it. The night after the floor platform was in place, Burt couldn’t sleep. As hard as he tried, he could not figure out what would make the walls stay up. He tried standing up a 2×4 board, but it kept falling over. But then he watched, fascinated, as the older boy framed the walls.

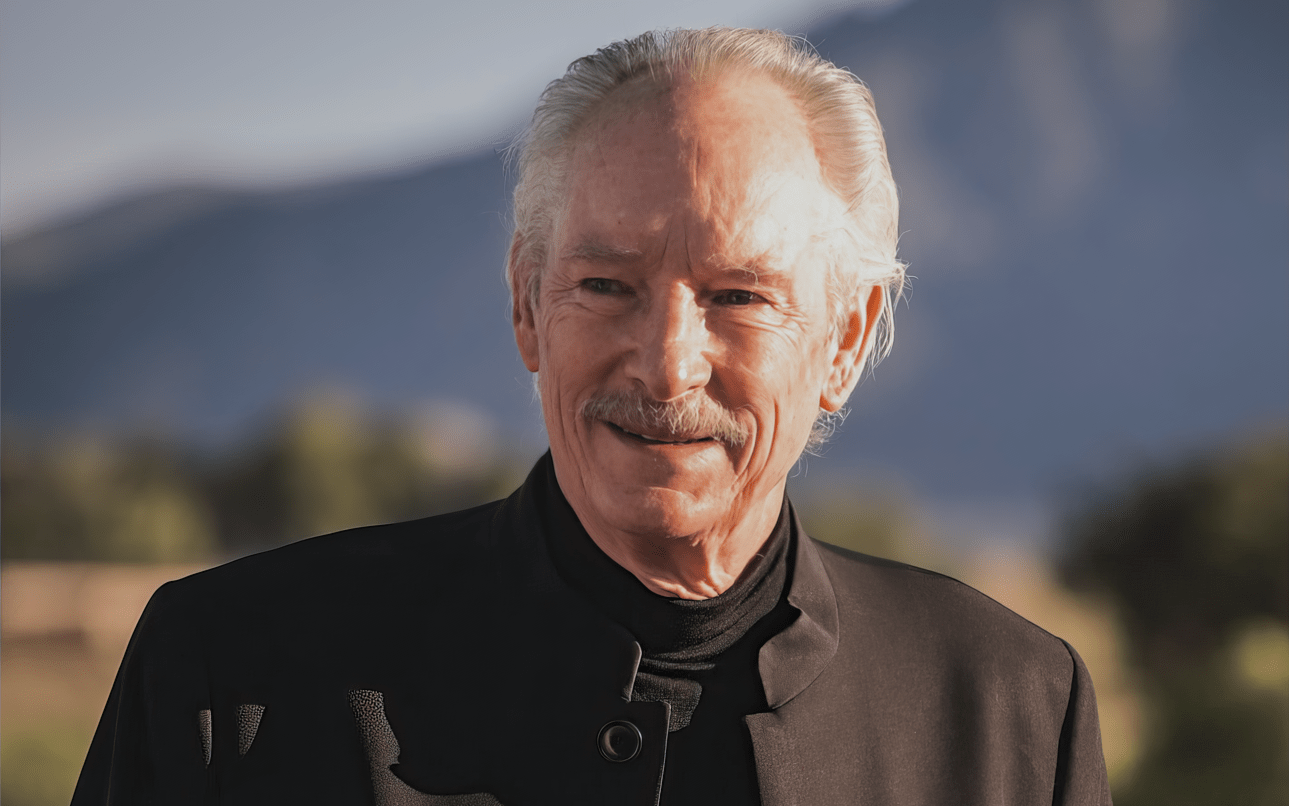

Looking back from the vantage point of an 82-year-old architect, Burt sees his early curiosity about building and his intense determination to figure it out as a telling precursor to a lifetime of dedicated, experiential learning, not only in his chosen profession, but also in understanding life itself. In the process, he has discovered countless ways that great architecture and the human spirit interweave as they serve and enrich each other.

An uncompromising interest

Burt was formally introduced to the world of architecture at age 15. His first summer job was as an office boy for the firm of the acclaimed Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei in Denver and then in New York City. He was struck by the architects’ manner, “their intelligence, professional posture, kindness, and humor. It set a standard for conduct,” he said.

He enrolled in the School of Architecture at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he and three fellow students “bonded irrevocably in an uncompromising interest in everything architecture,” he said. The four relentlessly self-educated, debated, and virtually lived in the design studio. But they soon realized their passion for architecture, including exploring radical design, was not welcomed by the staid, aging faculty. One by one, they were either kicked out or quit.

Burt dropped out in his sophomore year and made a pilgrimage to every Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house from Arizona to San Francisco. Then, broke, he landed a job as a dining salon worker on a Norwegian freighter that circumnavigated South America. It was during one port visit in Chile that he had a life-changing revelation.

He was walking amid the ruins of a 17th century Spanish fortress when one small section of stone wall stopped him in his tracks. “I can’t forget it. It was a very simple design,” he said. Sitting at the broad wooden desk in his home office/studio in the Grants, he picked up a pencil and sketched a wall that split into two half-circles to enclose a tree growing in its path, then came back together as a single wall. “This was human intelligence. This was great design, a Renaissance solution,” he said, adding that in that moment he realized he was part of that same timeless lineage.

Architectural and spiritual practice

He returned to school, obtaining his professional license in 1972 and embarking on an eight-year partnership with one of his former fellow renegade students, in the award-winning Boulder-based firm, Cooney-Wadman & Associates. In 1980, Burt established a solo practice, which continues today. Over the decades he has worked on urban design and New Town projects and designed residential, commercial, and retail buildings, as well as meditation centers in Massachusetts and London and a temple compound in Sarnath, India.

It is fitting that he was engaged in a design project in Sarnath, where the Buddha gave his first teaching after attaining enlightenment. The architect is not a practitioner of any specific wisdom tradition, but for almost 65 years, since reading Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi in his late teens, he has pursued a path of evolving consciousness with the same intensity of purpose that he applies to architecture. This pursuit has involved a series of esoteric teachers and 15 years as part of a spiritual community in western Massachusetts.

Local projects & a universal vision

In 2008 Burt’s wife, Marika Popovits, asked him to design a painting studio for her on an off-grid site in the Baca. The result is the couple’s home, which contains her studio and his office/studio. With passive solar heating, solar hot water, and electricity from the sun, Burt calls the design Helios 1. Informally, it is known as the “origami house” for its triangular planes and sharp angles, as if folded in paper.

Among Burt’s recent or ongoing projects: street improvements in downtown Crestone; a Community Services Master Plan for Crestone’s Tract 1, a Trails and Open Space Master Plan for the town, and a hike/bike trail to the Crestone Charter School; and in Alamosa, a master development plan for a large commercial complex that will include a children’s center for La Puente’s program for children suffering from neglect or abuse.

As an architect, Burt sees his strength in the ability to synthesize from many parts of life, including physical design, aesthetics, environmental context, and the utilization of natural energies. But there are also philosophical-spiritual elements—all converging in a singular vision. Indeed, the multidimensional nature of architecture is part of what drew him to the field as a young man and continues to keep him engaged. “Architecture is an art so vast in its technical diversity, economic complexity, and creative potential that it takes a lifetime to absorb a fraction of it and begin to find one’s own voice,” he said. In Burt’s continually-evolving visual language, light, space, and beauty are central. “When beauty is paramount and these criteria are employed, the structure itself becomes an energy receiver and transmitter within its local environment,” he said.

Reflecting on the broader role of architecture in human history, he added: “Great architectures allow us to believe in the nobility of the human spirit, to experience a sense of majesty, of awe, to invite our aspirations to soar, and occasionally, to get the scent of infinity. They communicate humankind’s passion for making and transmitting the precious legacy of beauty for its own sake.”