By Anya Kaats.

In 1992, Congress passed The Sangre De Cristo Wilderness Act, designating 220,803 acres of land as protected wilderness along the mountain range. In 2000, with the passing of The Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Act, another 50 square miles of land was converted to designated wilderness. Since then, several other tracts of land have been added, but 110,000 acres of land on the east side of the San Luis Valley (SLV) has yet to be officially designated and is “needing closure,” says Christine Canaly, long-standing director of the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council (SLVEC).

In a recent press release, SLVEC, an environmental organization that has worked tirelessly to protect the SLV ecosystem since 1996, announced that they will be pursuing a legislative opportunity to finally designate these remaining 110,000 acres as wilderness. SLVEC, which has been under the direction of Canaly for the past 23 years, cites the importance of “integrity and connectivity” for the landscape, and explains that if this new legislation passes, it will safeguard “unencumbered habitat for the land’s abundant wildlife, and ensure a cohesive ecosystem in perpetuity.”

“It’s difficult to accomplish anything longstanding from the top down. You have

to start from the ground up. Communities are the guardians at the gate.”

The Wilderness Act of 1964 defines wilderness as “an area where man is a visitor,” and only allows for “traditional land use,” including hiking, hunting, grazing, fishing, horseback riding, and camping. Motorized/mechanized transportation, and any activity that requires the use of machinery, explosives, milled timber, plastics, electricity, petrochemicals, metal, concrete or other modern materials, is strictly prohibited.

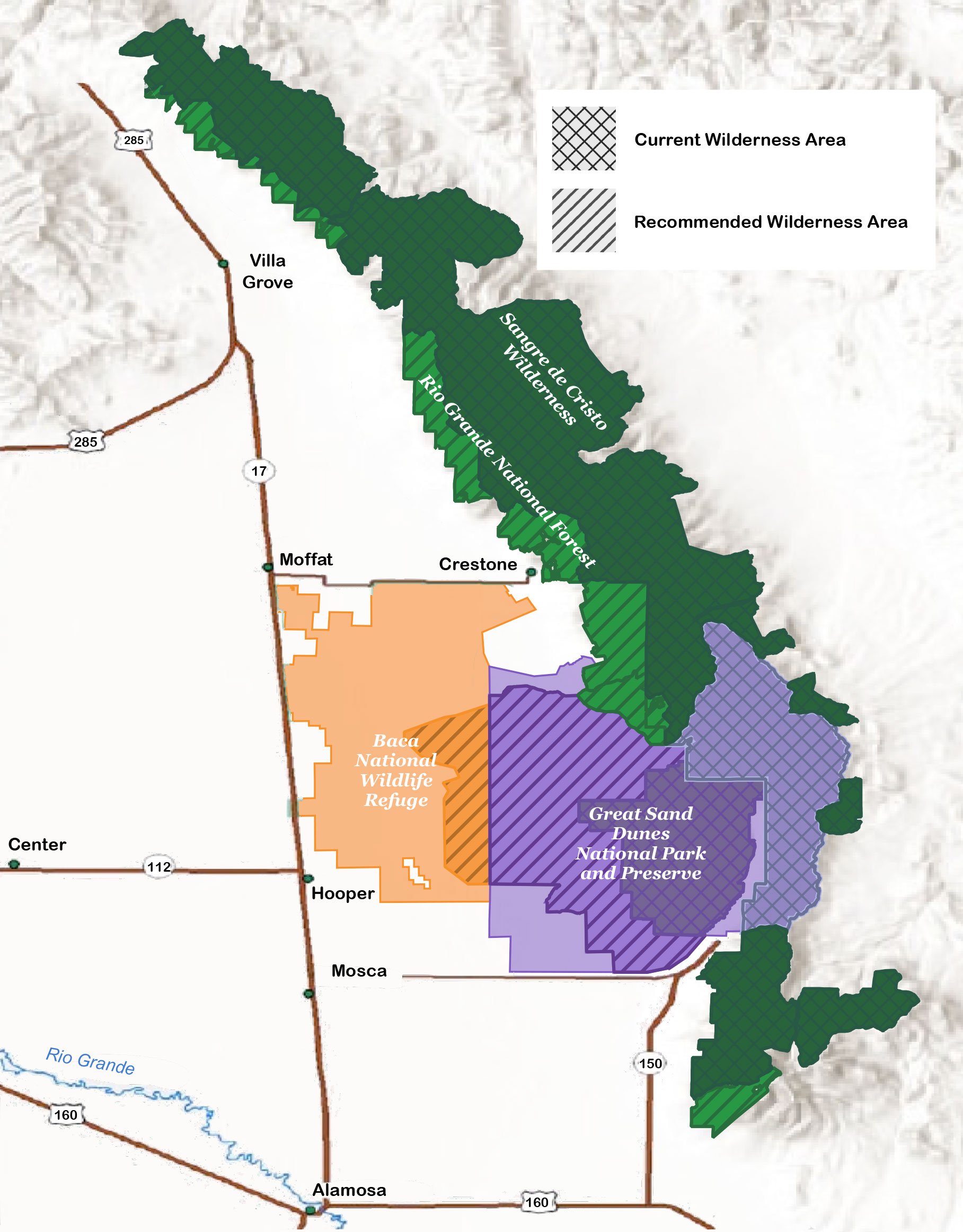

The 110,000 acres that have yet to be designated as wilderness in the SLV include a ribbon of land stretching 60 miles from Poncha Pass to the Great Sand Dunes along the Sangre de Cristo range, 50,000 acres within the Great Sand Dunes National Park, a 12,500-acre area within the Baca National Wildlife Refuge, and a portion of Mt. Blanca. The half-mile wide ribbon of land that runs down the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains was originally excluded from The Sangre De Cristo Wilderness Act because of unsettled mining claims. No longer encumbered by these claims, the Forest Service now has an opportunity to move forward with designating this section of land as wilderness. In conjunction with this designation, additional land managed by the National Park Service and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service that stretches out onto the valley floor has also been “recommended for wilderness” as a part of a bi-partisan effort to ensure consistency and cohesion.

SLVEC has been essential to the protection and preservation of land, water, and wildlife in the San Luis Valley for close to three decades. Their long and impressive list of accomplishments includes testifying before Congress to pass the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Act, spearheading a legal challenge to oil and gas drilling on the Baca National Wildlife Refuge, successfully challenging the massive real estate development proposal promoted by Leavell McCombs Joint Venture (LMJV) atop Wolf Creek Pass, and working alongside the Rio Grande Water Conservation District to stop a proposal by Renewable Water Resources (RWR), to pump 23,000 acre-feet of water (equivalent to 7.5 billion gallons) annually from the SLV to Douglas County on the Front Range.

In most parts of the country, this kind of environmental success story is unheard of, but Canaly believes that what holds us back has less to do with bureaucracy, and more to do with our tendency to become cynical and use it as an excuse to give up on what’s possible. “Cynicism has become comfortable, but it’s not a solution, it’s actually a burden, and it’s really important not to let it suffocate our passion,” Canaly explained. “I want to take that cynicism, unravel it, and propel it in a different direction,” she continued. “People are naturally curious and intelligent. Anyone can absorb almost anything as long as you take the time to explain it, so that they can assimilate it in their own way.”

Success, according to Canaly, relies on civic engagement and local cooperation. “It’s difficult to accomplish anything longstanding from the top down. You have to start from the ground up. Communities are the guardians at the gate,” she said. To get this most recent wilderness legislation passed, the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council is starting locally, asking for support from Saguache County Commissioners Liza Marron, Tom McCracken, and Lynne Thompson. Once the bill is introduced, it will be up to Congress to officially designate the 110,000 acres as wilderness and will require the U.S. President to sign it into law.

To learn more about the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council and to support their ongoing conservation efforts, visit www.slvec.org.

Image:

SLVEC is pursuing legislation that would designate an additional 110,000 acres of land along the base of the Sangre de Cristos and into the valley floor as wilderness. Map courtesy SLVEC