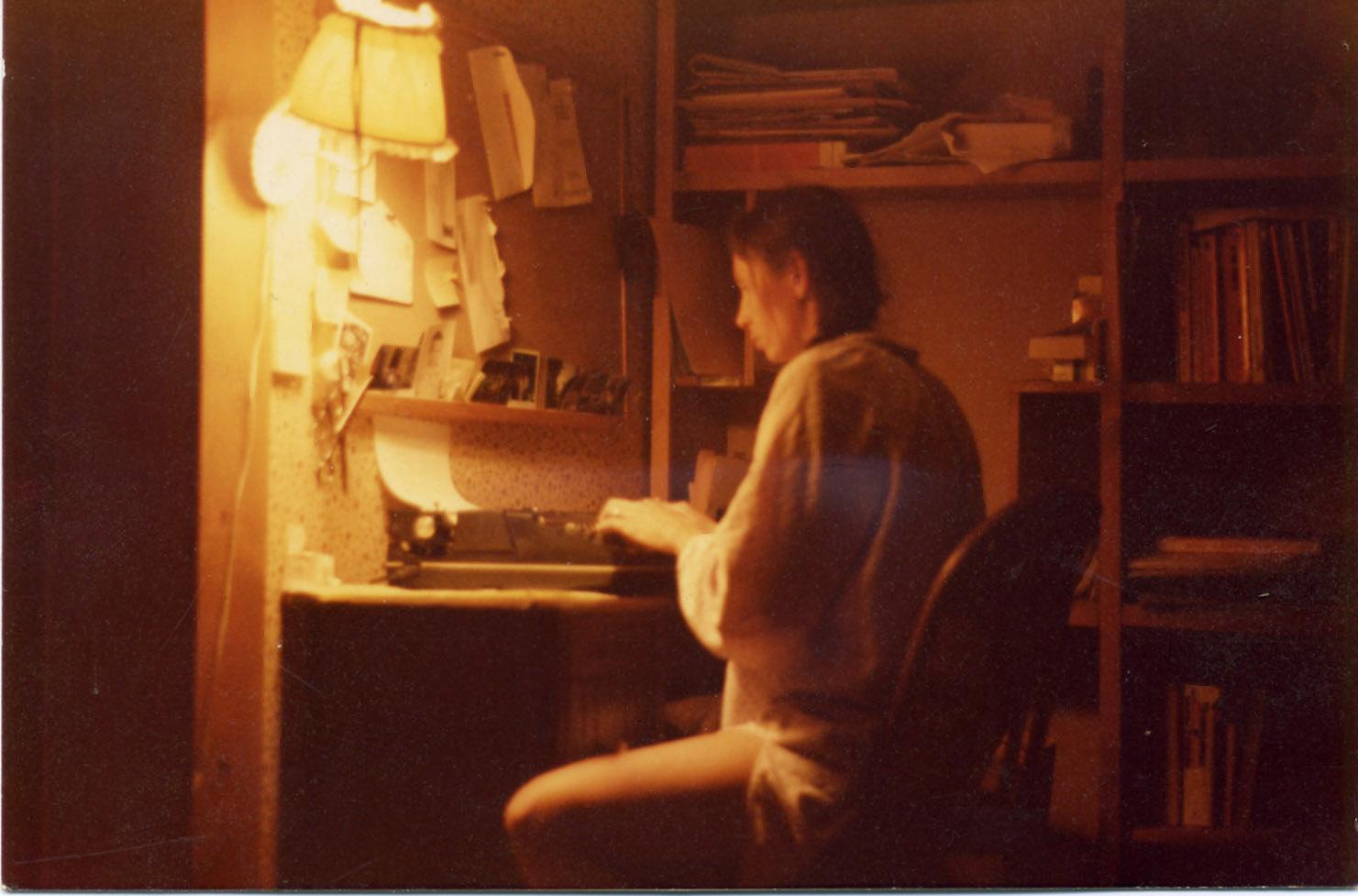

not getting good

grades in journalism.

1968.

If Kizzen Laki had any interest in journalism as a teen, her South Side Chicago high school journalism teacher extinguished it. He was also the typing teacher, and as a holdover of patriarchal conventions in those late-’60s days, he required all the girls to wear hose to class. He inspected their fingernails for perfect polish. He couldn’t stand Kizzen, and even though she was an excellent student and handed in A-worthy work, he gave her D-minus grades. “I was such a nongirl. He gave me terrible grades because I didn’t have the proper subservient girly attitude,” she says. Then she smiles, remembering how her sister Chris defended her when someone accused her of “dropping out” of society. Chris said simply: “She never dropped in.”

But she did find others who shared her unconventional ways, and places to thrive. Like Crestone. This fall, Kizzen is stepping back after an unplanned but deeply rewarding 33-year career in journalism, having established The Crestone Eagle in 1986 and developing it into a treasured community resource. She is selling the paper to Crestone Eagle Community Media (CECM), a local nonprofit that will continue what is most appreciated about it while expanding the Eagle’s news coverage, geographic range, and online presence. (More on this later.)

Carrying a heavy load

Not only did Kizzen’s initial exposure to journalism not spark any passion, but her early years held little hint of the profound connection with nature that has been at the heart of her life and spiritual path for more than half a century. She grew up thoroughly urban in a blue collar family with two older sisters. Their father worked as a machinist for the City of Chicago. More significantly, their mother suffered from multiple sclerosis and was confined to a wheelchair by the time Kizzen was 10.

For the next three years until her mother’s death at age 52, Kizzen and the sister still living at home were their mother’s primary caregivers. Kizzen gained strengths from the experience, learning to cook and other practical tasks while her mother directed from her wheelchair. “But it was a lot of responsibility on my shoulders at a young age,” she says, noting wryly that she’s undergone two shoulder replacements in recent years.

In keeping with her staunch Lutheran upbringing, Kizzen remembers herself as a good girl, a studious bookworm who never really got into trouble. Until later. As a teen she became a “child of the ’60s,” completely in synch with the counterculture. She attended concerts for the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix, took part in anti-war and civil rights marches, and was protesting in Lincoln Park during the 1968 Democratic Convention when tear gas-hurling police in riot gear swarmed the park. At the same time, beginning at age 16, she spent 10 years studying the Eckankar teachings, a mystical approach inspired by Eastern spirituality. It propelled her into an ever-evolving lifelong path that later incorporated earthbased wisdom. “Underneath, there’s always been a quest for self-realization and understanding of the grandeur. It’s an inner heartbeat of who I am,” she says.

A consequential time

On her 19th birthday Kizzen married Earl (“in the top 10 of stupidest things I’ve ever done”), and the couple hitchhiked to Las Vegas to attend an Eckankar conference, then caught a ride to Laguna Beach, California. She soon became pregnant but suffered a miscarriage at six months and almost died. An infection spread into major sepsis and she remembers floating outside her body above the VW van on the Coast Highway as friends rushed her to a hospital. Doctors attached an IV with a new type of antibiotic. It saved her life but gradually destroyed her hearing. The drug was later discovered to damage auditory nerves.

Although she loved the ocean, after her recovery Kizzen told Earl she wanted to go home. So they and a friend headed east. On the way, another life-altering event took place. Stopping in Buena Vista, Colorado, to visit an old family friend of Earl’s, they drove into the mountains, Kizzen’s first time in the Rockies. “It was the end of September, the aspens were golden, and the sky was this incredible blue like I’d never seen,” she says. As she sat beside Cottonwood Creek, she found herself sobbing, tears flowing for the first time since her ordeal. “I was wounded in my soul,” she says. Then, just as unexpectedly, she felt enveloped by an indescribable sense of grace. “I said to the guys: You go on, I’m staying. I’m home.”

Of course, they didn’t leave her; they all stayed. They lived as caretakers on a 1,000- acre ranch and then she and Earl moved into one of a cluster of rustic cabins in Chalk Creek Canyon, which they and other young people rented for $25 a month. They were there seven years, a period Kizzen has written about in her wonderful Mountain Mama stories for the Eagle, which she plans to continue and eventually compile as a book.

Shedding the urban

At Chalk Creek Canyon, she and Earl had a daughter and son, Nakia and Talmath. It was a labor-intensive life. She hauled water, chopped wood, raised her babies, and kept chickens, a burro, and goats—although after falling in love with the kid goats and then butchering them for food she became a vegetarian for 12 years. “There was such beauty and joy in that life and at the same time it was just so damn hard. We were so poor,” she says. It took years before she could look back and see the humor in some of it.

She divorced Earl, left the canyon, and she and her children moved into Buena Vista. She trained as an EMT, volunteered for the BV and Leadville ambulance services. took other courses at Colorado Mountain College, and generally re-entered the world. She completed aviation ground school in Leadville but couldn’t afford flight training, so her dream of flying never took off. In Buena Vista she met Mike Dennett, a carpenter. They married and had a son, Rama. In 1982, after the Climax Molybdenum Mine in Leadville cut production and the area’s economy faltered, Kizzen and Mike and their three children went looking for a new place to live.

Home to Crestone

They heard that Hanne Strong and her husband, Canadian oil developer Maurice Strong, owned several thousand acres in the foothills just outside the tiny former mining town of Crestone. Hanne was looking for young families to help realize her vision of establishing a community of diverse, authentic wisdom traditions and ecologically balanced living. She invited young people from places like BV and Alamosa to present her with a proposal, promising them free land. As it turned out, Maurice was not on board with the idea, so there was no free land.

But Kizzen and Mike had seen Crestone. They returned the following year, planning to stay a couple of weeks. “It was July and glorious,” Kizzen remembers. “Driving up that T-Road just felt like coming home.” When fall came they and the three children moved out of a tent and rented a house. Mike helped build the wooden Lindisfarne dome, now part of the Crestone Mountain Zen Center, and worked on several of the other spiritual centers being built at the time. They’d found their tribe.

Almost immediately, Kizzen was enlisted by the POA for her EMT skills. She was put in charge of the Baca ambulance service. She brought the sevice from basic life support rating to advanced life support. She served for 12 years before handing off the job to Pam Gripp. In 1986, the POA asked her to edit its monthly member newsletter. Needing income, she reluctantly agreed, then discovered she enjoyed it. Before long she changed the layout and font. She began adding stories not directly related to the POA but of interest to local folks, including news of a major water-grab threat, which the community successfully fought. The POA board wasn’t happy about the non-POA news, but POA Manager Petie Lipscomb liked it. She proposed that the POA sell Kizzen the newsletter for $1. Kizzen agreed, taking the Eagle’s name from one of two newspapers published in Crestone in 1901. She couldn’t pay herself a penny for the first three years. When she and Mike divorced, she moved the Eagle office from their home to a small office where the marijuana shop now is and then to its current downtown building, shared by the Crestone Artisans Gallery.

Before long, local resident Janet Woodman noticed that the paper was in serious need of a proofreader. She stopped by to offer help—and stayed. An artist herself, she created the Eagle logo design and over the years has done almost every job at the paper other than Kizzen’s. “I’m the front-man and Janet just quietly gets things done. We’ve made a really good team,” Kizzen says. The two are now married.

For Kizzen, putting out the Eagle every month has been an expression of dedicated service to the community and an act of co-creation with the community. From the beginning, local residents have contributed writing and photography for free or minimum pay, allowing the paper to continue and grow. Kizzen will remain involved through its transition to nonprofit, working alongside new editor John Waters and general manager Jennifer Eytcheson for at least the first few months under CECM ownership.

Kizzen’s deep love for this place has also seen her serve for 25 years as a member of the Crestone Town Council and as mayor for ten years. She helped get the Crestone Music Festival going, started the Cabin Fever talent show, and initiated the first community Thanksgiving potlucks and Christmas parties. A favorite accomplishment: She has overseen the planting of at least 70 trees in the town parks and along rights-of-way. It’s no surprise that she quotes the words of the late Bertha Gotterup, beloved local ceramic artist, who responded when asked about her religion: “I’m standing on it.”

No surprise either that among Kizzen’s passions are gardening and getting out in the mountains with Janet in their camper trailer, for which they will soon have more time. Plus spending time with her 3 children and 5 grandchildren. “They light up my life”, she says.

Sitting at the wooden kitchen table in their off-grid log home, one arm in a sling from shoulder surgery a week earlier, she reflects on what brought her here all those years ago and what keeps her here. Along with the area’s extraordinary beauty and quiet, she says, “More than anything, it’s home. We’re always gonna have challenges, but I’ve seen that when we come together over important things, amazing things get done. There’s a wellspring of creativity and spirituality that’s here, and I’m in love with that.”